“Gender pay gap is the average difference between hourly wages for men and women”

Gender pay gap is a measurable indicator of inequality between women and men. Most governments have legislated to guarantee equality of treatment between men and women in remuneration, like during the “ILO Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100)”. This principle has also been reaffirmed in target 8.5 of Sustainable Development Goal 8 on promoting inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all, stipulating that, by 2030, countries should “achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men….” (1)

Are gender pay gap and health connected? Indirectly yes. The fact that women are paid less and, in some cases very much less, often doesn’t allow them to have equal health choice possibility. Especially in countries with a private health system, the lack of women economy empowerment and gender pay inequalities force women to get health services based on their income and not based on their personal choice.

Here some data to understand the contest:

- The gender pay gap persists and globally is estimated to be 23 per cent, meaning women earn 77 per cent of what men earn (2) .The World Economic Forum estimates it will take 202 years to close the global gender pay gap, based on the trend observed over the past 12 years (2; 3; 4; 12).

- Women in the EU are less present in the labour market than men with 67.3 % of women across the EU being employed compared to 79% of men (EU27 data). Always in EU, the gender pay gap stands at 14.1% ( meaning women earn 14.1% on average less per hour than men).

- The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that women on average continue to be paid about 20 per cent less than men across the world. There are large variations between countries, from a high of over 45 per cent to hardly any difference (see figure 1). The gender pay gap has been reduced in some countries while in others there has been little change.

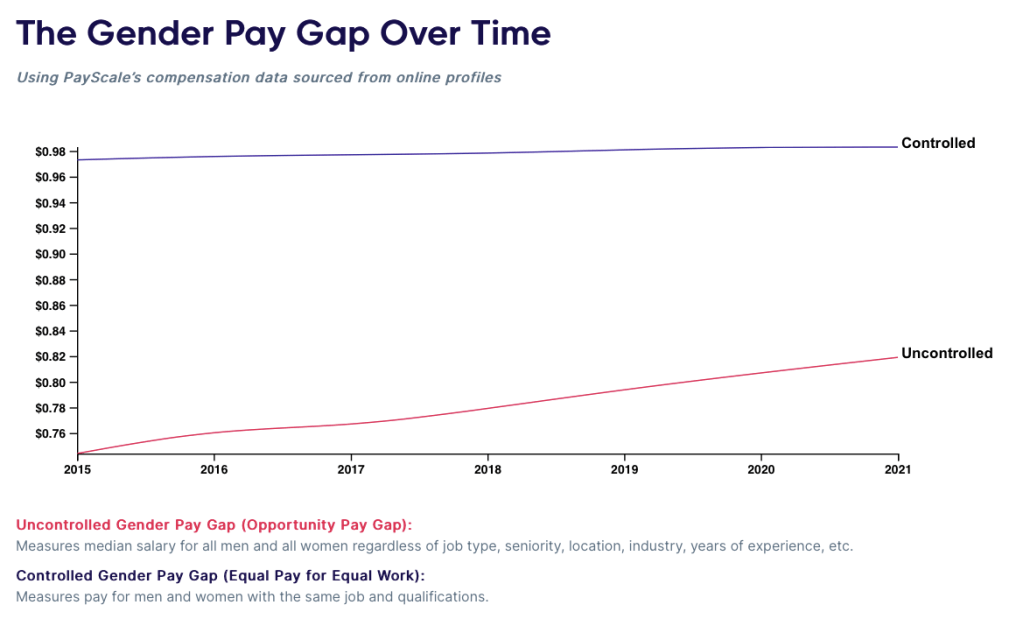

- In the U.S. the uncontrolled gender pay gap ( median salary for all men and women regardless of job type, work seniority and other factor), has decreased by $0.08 since 2015. In 2021, women make only $0.82 for every dollar a man makes

- The controlled gender pay gap (pay for men and women with the same job and qualifications) decreased since 2015, but only by $0.01. Women in this group make $0.98 for every $1.00 a man makes, meaning that women are still making less than men even when doing the exact same job (3)

Why do we still have gender pay gap (5)?

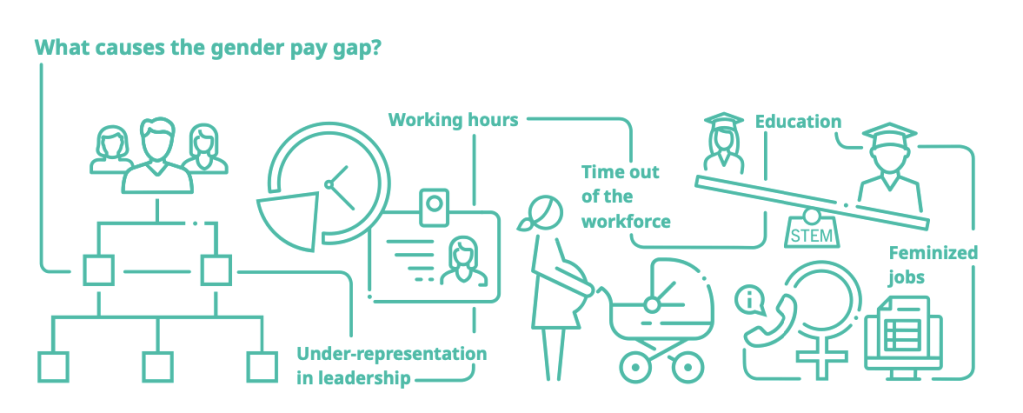

- Occupational segregation is one large driver of the overall pay differences between men and women. “Women and men are confined to certain occupations and stereotypes are strengthened regarding women’s and men’s aspirations, preferences and capabilities. In turn, this affects both the perceptions of employers about women’s and men’s skills and attitudes and the aspirations of individual workers”. Women and men are likely to continue pursuing careers in sectors and occupations that are considered “feminine” and “masculine” and are discouraged to do otherwise (6; 7). Women are more likely to be concentrated in lower-paid occupations and sectors than men (8; 9; 10; 11; 12; 13) and consequently, sectoral and occupational segregation inhibits the opportunities and choices that women and men have in pursuing different types of work.

- Under-representation in leadership: Very few women are in management and leadership positions, especially at higher levels. When women are managers, they tend to be more concentrated in management support functions such as human resources and financial administration than in more strategic roles.

- Working hours: The gender pay gap is often a consequence of the different patterns of workforce engagement by women and men. In the “Global wage report 2018/19: What lies behind the gender pay gaps”, the ILO highlights that women work on a part-time basis more than men do. This is often linked to women taking on more of the unpaid family responsibilities.

- Time out of the workforce: Women more than men are likely to take career breaks from their employment in order to raise children or care for the older or ill members of the family.

- Education: Even though women are surpassing men in most regions as tertiary graduates, and they are advancing into the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) disciplines, they are still lag behind men in STEM areas that are associated with higher paid jobs. Even when women are qualified in STEM subjects, it can be challenging for them to obtain and maintain a job in these areas because they are traditionally male dominated.

- The uncontrolled pay gap even reveals the overall economic power disparity between men and women in society. Even if the controlled pay gap disappeared the uncontrolled pay gap could persist if high paying positions were disproportionately accessible to men.

- The overall differences in women’s and men’s pay and career outcomes goes beyond gender preferences and can only be explained holistically through gender and racial bias. In other words, a woman who is doing the same job as a man, with the exact same qualifications as a man is still paid two percent less for no attributable reason.

These differentials in earnings between women and men are a policy concern, as many of the factors that cause the gender wage gap are consequences of broader gender inequalities. These aspects all have a direct impact on overall earnings and life for women as:

- to be more likely unemployed than men.

- to be over-represented in low-wage jobs informal and vulnerable employment.

- to bear disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care and domestic work.

- to become less likely entrepreneurs and face more disadvantages starting businesses: Only 5% of Fortune 500 CEOs are Women (14).

- to have a gender pay gap widens with job level and age: the pay gap widens as women progress in their career, with women at the executive level making $0.94 to every dollar a man makes even when data are controlled. Women also tend to move up the career at a slower pace than men (opportunity gap).

- the assumptions about what kinds of work women are best suited for, often based on gender norms and funneling women into lower-level and lower-paid positions or face the motherhood penality. This makes women to be perceived always as potential mothers or carers and they may be overlooked when more challenging assignments or even promotions are made. Consequently, employers may practice what could be termed “statistical discrimination”, by assuming that all women expect to interrupt their careers, show less interest in training to improve their skill-sets and are less likely to take positions where the compensation is future-loaded (15; 16). Discrimination against pregnant workers and workers with family responsibilities – or “maternity-related discrimination” – is a pervasive problem around the world, causing the so called “maternity harassment” (the practice of harassing a woman because of pregnancy, childbirth, or a medical condition related)

- Men are likely not to experience a penalty but instead a compensation after becoming parents and earn more than their childless peers (16;15; 17)“fatherhood wage premium”.

This stubborn inequality persists in all countries and across all sectors and, become worst with a wider gap if we talk about women of color.

“Women of all races and ethnic groups earn less than white men. The largest uncontrolled pay gap is for American Indian and Alaska Native women, black or African American women, and Hispanic women. These women earn $0.75 for every dollar a white man earns, which improved by $0.01 from 2019” (4)

Women of color face greater barriers to advancing in the workplace compared to white women and they even start out further behind and the pay gap for them also get worsens with career progression.

Many pay gaps seen by women of color have widened since last year, a possible result of pay cuts or unemployment disproportionately affecting these women amidst COVID-19.

Countries around world are trying to reduce this gender, ethnical and cultural differences through legislation ( as the US Equal pay act in 1963 and the UK Equal pay act 1970). And, considering that ILO noted that, without targeted action, at the current rate, pay equity between women and men will not achieved before 2086 there is still a lot of work to do!! There has been a slight improvement since 2015 And even though the journey is long and we don’t still have the tools to the radio change, we definitely know the area where governments, policies and legislation should work more:

- Economic Empowerement: Women’s economic empowerment is central to realizing women’s rights and gender equality and womens’ economic empowerment allow women to participate equally in existing markets to have access to and control over productive resources, to have access to decent work and have control over their own time, lives and bodies, increasing their voice, agency and meaningful participation in economic decision-making at all levels from the household to international institutions. Empowering women in the economy and closing gender gaps in the world of work are key to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (18) and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 5, to achieve gender equality. When more women work, economies grow.

- Education: Increasing women’s and girls’ educational attainment contributes to women’s economic empowerment and more inclusive economic growth.Increased educational attainment accounts for about 50 per cent of the economic growth in OECD countries over the past 50 years (19).

- Work equality: Women’s economic equality is good for business. Companies greatly benefit from increasing employment and leadership opportunities for women, which is shown to increase organizational effectiveness and growth. It is estimated that companies with three or more women in senior management functions score higher in all dimensions of organizational performance.

- Eliminating unequal treatment of men and women in the labour market: clear legislative frameworks ensuring that women have equal access to labour market participation and protection from all forms of direct and indirect discrimination and harassment. In addition, policies that prevent discrimination of workers based on gender, maternity, paternity and family responsibilities and providing formal structure that remove barriers to employment and career progression.

- Promoting equal pay for work of equal value: Through wage transparency, training and gender neutral job evaluation methods. In some countries, laws and regulations refer only to equal pay for “identical” or “similar” work rather than for work “of equal value”.

- Supporting adequate and inclusive minimum wages and strengthening collective bargaining.

- Promoting and normalizing good quality part-time work.

- Changing attitudes towards unpaid care work to overcome the motherhood wage gap: This raises a fundamental question regarding the role and impact of work-family policies in recognizing, reducing and redistributing unpaid household and care work and enabling women to enter, remain and make progress in the labour force.

Gender pay gap is a topic that involves many sectors and requires a political, social and cultural effort to achieve. We might still not have the tools to close the gap, but searching, reading and talking about it, it’s a start to raise the awareness and begin the journey.

References

1- A new era of social justice, Report I(A), International Labour Conference, 100th Session, Geneva, 2011 (Geneva).

2- https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—act_emp/documents/publication/wcms_735949.pdf

3- https://www.payscale.com/data/gender-pay-gap

4- World Economic Forum: The Global Gender Gap Report 2018 (Geneva, 2018), p. 15.

5- https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—act_emp/documents/publication/wcms_735949.pdf

6- Catalyst. 2005. Women “take care,” men “take charge:” Stereotyping of US business leaders exposed (New York)

7- https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/au/pdf/2019/gender-pay-gap-economics-full-report-2019.pdf

8- Burchell, B.; Hardy, V.; Rubery, J.; Smith, M. 2014. A new method to understand occupational gender segregation in European markets (Luxembourg, Publication Office of the European Commission).

9- ILO, 2012a. Global Employment Trends for Women (Geneva).

10- ILO, 2010a. Women in labour markets: Measuring progress and identifying challenges (Geneva).

11- ILO, 2009. Gender equality at the heart of decent work, Report VI, International Labour Conference, 98th Session, Geneva, 2009 (Geneva).

12- Verashchagina, A. 2009. Gender segregation in the labour market: Root causes, implications and policy responses in the EU (Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union).

13- Charles, M. 2003. “Deciphering sex segregation: Vertical and horizontal inequalities in ten national labor markets”, in Acta Sociologica Vol. 46, pp. 267–287.

(https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/equal-pay

14- https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures#notes

15- Rubery, J 2015. “Austerity, the public sector and the threat to gender equality”, in The Economic Social Review, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 1–27.

16- Grimshaw, D. 2015. Motherhood pay gap: A review of the issues, theory and international evidence (Geneva, ILO).

17- Budig, M.J. 2014. The fatherhood bonus and the motherhood penalty: Parenthood and the gender gap in pay (Washington DC, Third Way).

18- https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/equal-pay

19- OECD, Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship: Final Report to the MCM 2012. http://www.oecd.org/employment/50423364.pdf p. 3.