With the all the conversations about inclusivity and diversity in the last period, even the medical community has been found to be guilty.

When talking about the findings of research studies, one of the main goals to achieve is to have a “representative” result of what happens in the reality. Meaning that, what we discover should be as much as near to what happens in the world, sustainable and near to the reality. Obviously to achieve those studies should be done with a big and heterogeneous sample of people from different ethnical, social, religious, and economical background. But this should not only be related to research, but even the academic and practice area.

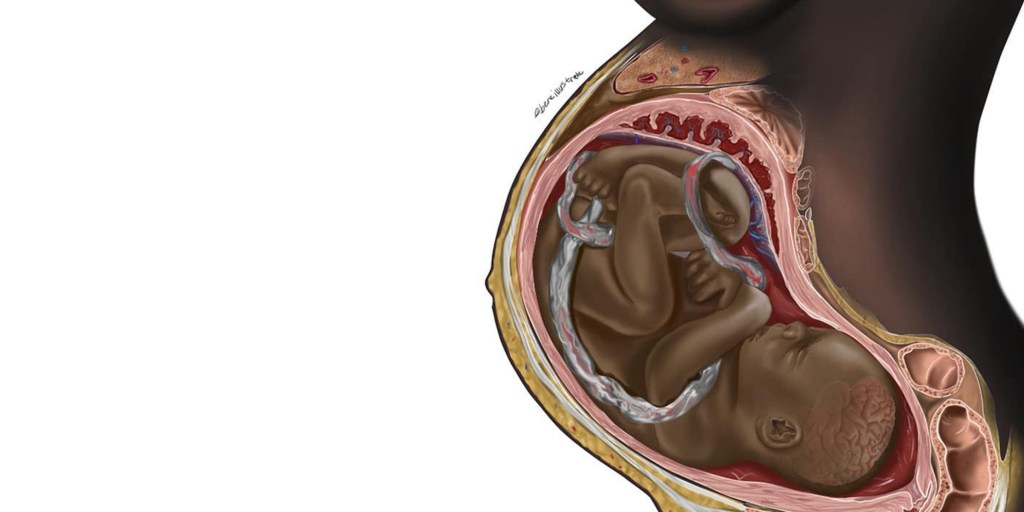

Science represents the real world made of a variety of people. It is not an easy task to gain but for long time this issue has not been addressed, and what we have now is that of 2022. We had the first illustration of a black foetus by medical student Chidiebre Ibe shocking the world but at the same time making everybody understanding that changes should be made.

Although the under-representation of dark skin population in the medical field is an issue that affects training in every branch of medicine, it is definitely problematic for dermatology where the diagnosis, prognosis and assessment of the severity of a condition depends almost entirely on the appearance of the skin. Dermatology has suffered a lot of under-representation and lack of diversity.

Dermatology has historically been very “Euroncentric” with learning materials referencing the “normality” of only a lightly pigmented skin. But the global population is ethnically diverse and unfortunately the understanding of dermatology is not always accurate for the people with black and brown skin. This leads to misdiagnosis, poorer outcomes and poorer treatment for people with dark skin.

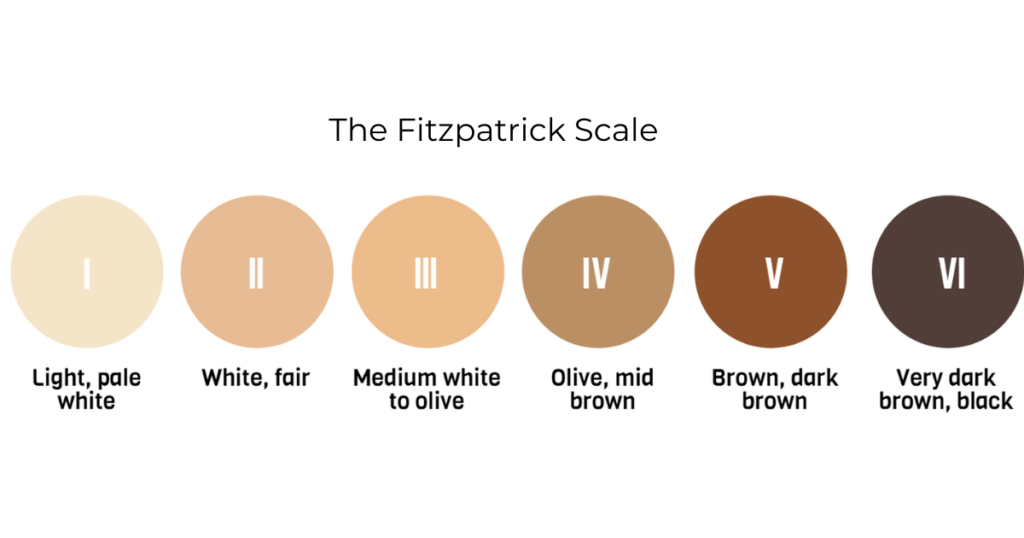

But to address the issue, we have to go back in the time, particularly in 1975, with the Fitzpatrick skin type classification, used till now from dermatologist and where the skin type V and VI have been added only in the 1988.

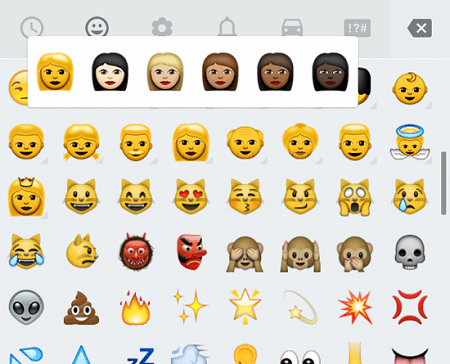

Just from a quick view of these ranges we can immediately detect the bias and under-estimation on skin variants and possible biases in the clinical settings. The main problem is that, this classification has not been changed if not updated and many other programs use it till today (for example; WhatsApp emojis).

This causes that a continuing problem in dermatology teaching to be biased:

- A study published in 2018 reviewed over 4,000 images in textbooks that are commonly used in top medical schools, such as The Atlas of Human Anatomy and Gray’s Anatomy for Students, founding that only 4.5% of images represented dark skin tones (Louie, P. & Wilkes, R. (2018). Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery. Social Science & Medicine, 202, 38-42.)

- Lester’s analysis found that while 28% of images of infectious diseases used images of darker skin, the number of depictions of dark skin was twice as high for infections that were sexually transmitted.

- A simple google search demonstrates a similar bias: a review of images in two commonly used dermatology textbooks found that while 22-32% of images depicted skin of colour, darker skin was more likely to be used to illustrate sexually transmitted disease, accounting for 47-58% of these images. (Lester JC, Taylor SC, Chren M‐M. Under‐representation of skin of colour in dermatology images: not just an educational issue. Br J Dermatol 2019; 180: 1521–2.

For years, physicians and medical students, most of them who are people of colour, have tried to raise the awareness of this problem, to highlight the scarcity of images of black and brown people in medical curricula, reporting inadequate training in identifying conditions on dark skin and seeing the need for greater exposure to images of people of colour in training materials. It is paradoxical that while the formal medical course emphasizes on equality of care, this message is not translated by the medical textbooks, case studies and training materials characterized by a poor representation. Furthermore, this under-representation that places a white person as the normative patient has been identified as a significant contributor to racial inequality in health care experience, treatment, and patient outcomes.

What can be done? And what has is happening now regarding this issue?

- As many have already done and still continuing doing, raise the problem! It is important to raise the need of a more comprehensive, inclusive and diverse educational resources. This should be done not only in the dermatology field, but in all.

- Another important thing, share your concern with other colleagues, medical associations, and professors. You might find out to have many people that will support you and share the same cause.

- Educate yourself: one of the good things about internet and social media is that there are many resources out there. And even though it might be hard to understand if a resource is the right one, ask for others opinions and feedback from other professionals.

- Create your own space or tools to highlight this problem: Malone Mukwende , a second year medical student from St. George’s Medical School in London, co-wrote a handbook named Mind the Gap, which aims to raise awareness on how symptoms and signs of conditions can manifest differently on dark skin; Brown Skin Matter is another Instagram page with reference images of dermatological conditions on non-white skin, aiming to help people of colour identify skin conditions; to solving the problem of standardized images to be used in training that illustrates how signs manifest and progress with disease severity across different skin type and overcome the poor image resolution available at the moment, Signant Health gathered a multidisciplinary team of graphic artists, scientists, and expert clinicians to develop a set of training images for clinical research, capturing the progression of the signs of atopic dermatitis in common anatomical areas affected by the condition. Training on such a diverse set of images has the potential to increase the reliability of clinician reported measures in dermatology clinical trials.

These online movements demonstrate that, unlike other pervasive economic, historic, and cultural barriers to health for people of colour, the under-representation of dark skin in training materials can be remedied. By improving the tools and education provided to clinicians, we can achieve improvements in diagnosing and treating skin conditions in people of colour and give the correct and deserve care to all.

And from the women point of view? We will discuss it in the next article!!